By: Lisa Brown, Malathi Mahadevan, and Daniel Sato

Department of Communication, University of Delaware

COMM706-610: Communication Theory

Professor Emily Pfender

Synthesis of Literature

Fossil fuel usage, and the climate science behind its impact on the environment, touches upon a wide range of topics. In synthesizing literature research compiled by the Fossil Fuel Fighters, five common themes rose to the surface. Research revolved around perceptions of climate change, climate friendly behaviors, attitudes toward renewable energy, attitudes toward fossil fuels and climate change misinformation.

Perceptions of climate change, whether it has been accelerated by human interference and the severity of the problem, vary widely depending on a number of factors. Research found that political affiliation plays a major role in perception of climate change (American Psychological Association, APA Task Force on Climate Change, 2022). Also, studies found that those with a greater concern for the environment typically knew more about the environment and were willing to pay more for renewable energy than those not concerned about the environment. However, this concern for the environment did not translate into knowledge of actionable steps to help (Bang, H.K., et al., 2000).

One major factor shaping attitudes toward climate change is misinformation. A 2022 American Psychological Association Task Force on Climate Change highlighted this issue. “Most prominent are sustained efforts by the fossil fuel industry since the 1960s to mislead the public and policymakers about global warming and to lobby against changes in laws (e.g., tax subsidies) that favor use of fossil fuels” (American Psychological Association, APA Task Force on Climate Change, 2022, p. 10). Studies also pointed to “greenwashing” of climate data, in which companies position themselves as climate friendly through media and communication campaigns, but actually contribute to climate change (Benjamin, et al., 2022).

Climate friendly behaviors were found to increase when campaigns associated climate inaction with consequences personal to the target audience. Researchers in Vietnam found it effective to frame the risks of climate change around health risks that could result from rising temperatures. This included an increase in heat stroke, vector-borne diseases such as dengue fever and blue algae blooms (Nguyen et al., 2018). A study of sustainable food systems found that women have a higher intention to behave in a climate-friendly manner when it comes to the food they purchase. Also, people 30-years-old and older were more likely to intend to behave in a climate-friendly manner than those younger than 30. Researchers emphasized the need to sensitize individuals to the connection between their diet and climate change (Emberger-Klein et al., 2021).

Studies focused on attitudes toward renewable energy found that cost prevented the public from increasing renewable energy usage. Emberger-Klein et al. found “the need to contribute to climate protection is lowest for people who have never been employed” (Emberger-Klein et al., 2021, para. 14). This idea was repeated in further studies that discussed cost when examining attitudes toward renewable energy. A 2007 Swedish study found that while a willingness to pay for green energy increases with a positive attitude toward green energy, increased electricity costs decrease that willingness to pay (Hansla et al., 2008).

Attitudes toward fossil fuels were tied to local impact and individual identity and freedom. In some cases, local economies are based around fossil fuel extraction and production. Residents in these cities have a negative attitude toward renewable energy development because it is viewed as a threat to the local economy and, at times, runs contrary to one’s individual identity (Olson-Hazboun, 2018). A 2014 study that looked at Canada’s Northern Gateway Pipeline compared attitudes toward the project in Canadians in Alberta and British Columbia. Differences in attitudes were seen based on location; with those in Alberta more likely to support the project and look to economic benefits, and those in British Columbia more likely to oppose the project and look to environmental impact (Axsen, 2014). Researchers studied Pittsburgh, a historically blue-collar town, to gauge attitudes toward limiting SUV and trucks and promoting green energy. Respondents disapproved of any hard regulations, whether framed as having a positive environmental impact or necessary for national security, because the regulations impeded on their personal freedoms. Instead, respondents favored voluntary action or soft regulations (Attari, S. Z., et al., 2009).

Reducing fossil fuel usage will be crucial in preventing or limiting the long-term effects of climate change. A synthesis of literature research showed that the cost of switching to green energy is one of the major impediments to switching in the minds of many. However, campaigns can have an effect on attitudes toward climate change if the risks around climate change are framed in a way that is personal to the target audience and those with a positive attitude toward green energy or a concern for climate change were more likely to engage in climate friendly behaviors.

Campaign Goal

In 2021, the United States got 61% of total US primary energy needs from fossil fuels (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2022). These fossil fuels, like coal, oil, and natural gas are then burned to generate power, releasing carbon dioxide, which causes climate change (Zhang & Caldeira, 2015). Island communities tend to be the first and most negatively impacted by climate change (Lazrus, 2012).

Based on a study by Leeds University (Oswald et al., 2020) wealthy people consume more energy and are responsible for more fossil fuel usage compared to less wealthy people. In Dukes County, MA, 80% of homeowners have their home completely paid off, and 77% of homes cost $500,000 or more (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). This tells us that there is an area where people are affluent, and have the income to spend on switching to renewable resources.

One way to switch to renewable energy is to call the local energy provider and have them switch the home’s supply from fossil fuels to a renewable resource. Based on a study by Oxford University, (Way et al, 2022), switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy could save the world as much as $12tn by 2050. While gas prices have risen steadily due to mounting concerns over energy supplies, researchers say that going green now makes economic sense because of the falling cost of renewables.A Pew Research study (Tyson, 2022) indicated that 71% of U.S. adults consider it important to make the move from using fossil fuels to using nature based renewable resources. This step is also a key component of President Joe Biden’s climate and energy policy agenda. Research has also suggested that people can have general concerns for causes without having it translate to personal concerns (Zander, 2018). There may be more motivation needed to act on it at a personal level – and that’s what our campaign tries to address.

Our campaign goal, therefore, is to get 50% or more of households that are still using fossil fuels in a largely democrat leaning target audience to switch to renewable resources within the next six months.

Target Audience

Our target audience is affluent, liberal-leaning individuals who live on Martha’s Vineyard Island, Massachusetts. They are likely to be easily persuaded by our message to reduce their fossil fuel usage by having their energy provider switch their energy to renewable resources.

Many factors affect how people view climate change. Both political affiliation and misinformation play a significant role in an individual’s feelings toward climate change (American Psychological Association, 2022, p. 8-9). Climate Change Countermovement Coalitions work to spread misinformation and disinformation about climate change (Brulle, 2019).

We are targeting individual action as opposed to government legislation because, according to Millard-Ball (2012), the environmental choices of citizens drive emission reductions more than structured climate action plans.

Consumers who are more concerned about the environment are more likely to pay more for renewable energy (Bang et al., 2020, p. 449). Because liberal-leaning individuals already believe that climate change is an emergency (Gregersen et al., 2020), they will be more likely to pay for renewable energy. Therefore, our target market will be highly likely to take action because the residents of Dukes County, where Martha’s Vineyard is located, voted 77% for Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election (PD43+, 2020).

A major reason people don’t convert to renewable resources is because of the cost (Lei et al., 2011). By focusing our efforts on an affluent community in Massachusetts, a state which already has the second highest household net worth in the country (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020), we remove this financial barrier in convincing people to switch to renewable resources.

It’s also important to note that while Gen Z and Millennials believe climate change is more of an urgent threat than Gen X and Boomers, this discrepancy exists primarily within the Republican party. According to Tyson et al. (2022), “attitudinal differences by generation among Democrats are less common, as large shares prioritize climate action and back policies to help reduce climate impacts” (para. 11). So, for this proposal, we will focus on the highly Democratic makeup of Martha’s Vineyard to tap into the desire to prioritize climate action.

As the theory of reasoned action teaches us, as more of their peers switch to renewable resources, more residents will likely follow suit (Perloff, 2017, p. 164-167). So, by targeting a tight-knit and highly-democratic community, with a large number of residents who make climate change a priority, individuals are more likely to be influenced by the subjective norms in their community by switching their electric provider to renewable energy sources.

By targeting homeowners on Martha’s Vineyard, we are focusing on a specific group of people with a high motivation to process our message, because their island, homes, and way of life are at the forefront of climate change (Forbush & O’Shea, 2021).

That is why we will target wealthy, liberal-leaning individuals living on Martha’s Vineyard Island, Massachusetts to switch their energy source to renewable resources.

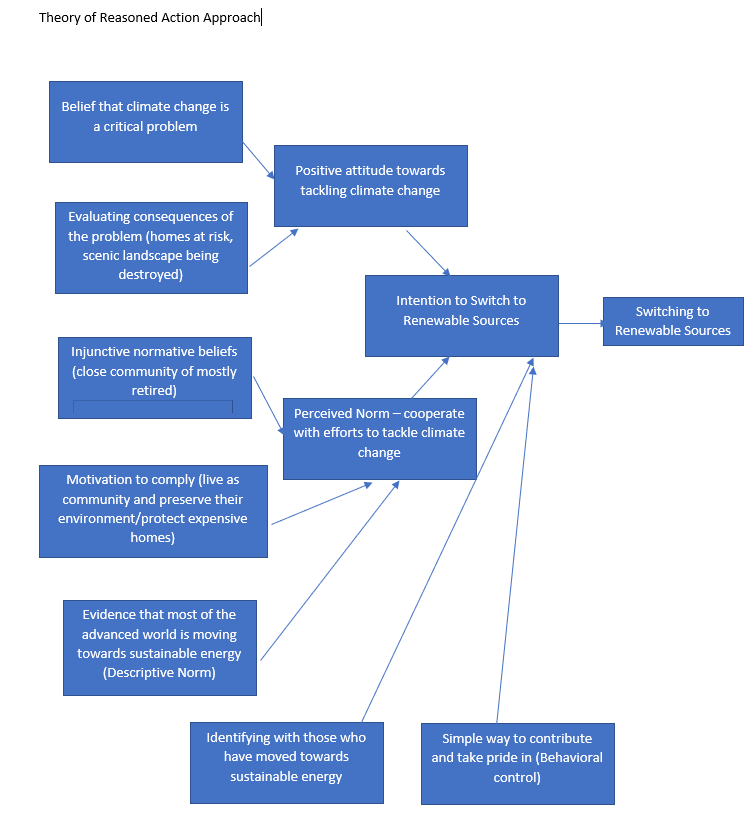

Theory of Reasoned Action

Using Theory of Reasoned Action, the behavior that we are trying to target is to get 50% or more of households that are still using fossil fuels in the target audience to switch to renewable resources within the next six months. It’s not likely something our target audience is currently intending to do because calling your electricity provider is such a simple behavior that it’s not something you would plan to do, it’s something you would just do.

First, we look at the predictive constructs around this behavior. When looking at attitudes our target audience has toward this behavior, most of our target population is Democratic, and therefore likely thinks that switching their electricity to renewable resources is a good thing (Gregersen et al., 2020). Looking at the predictive construct of subjective norms, their neighbors also likely think that switching to renewable resources is a good thing, as Dukes County voted 77% for a Democratic candidate, and Democrats are more likely to worry about climate change (Gregersen et al., 2020; PD43+, 2020).

Now, we unpack the attitude toward the behavior. Our liberal target market associates doing environmentally friendly things with the act of switching to renewable energy, and they think that using renewable energy is a very good thing (Gregersen et al., 2020; PD43+, 2020). They have a very positive behavioral belief associated with switching to renewable energy.

Then, we unpack the behavior toward the subjective norms. Normative beliefs behind this behavior is that neighbors and other residents of Martha’s Vineyard think that switching to renewable energy is a good thing. Because the entire island primarily caters to wealthy tourists (Pollak, 2012), the community’s way of life, including the existence of their incredibly expensive beachfront homes is at risk. In fact, according to Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s Island Plan (2010), the island has over $18 billion of property. Because of this most of the island would want everyone around them to switch to renewable energy to reduce the effects of global warming. Making the switch to renewable energy is certainly something we can see the residents of Martha’s Vineyard encouraging their neighbors to do as well. In fact, Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s Island Plan (2010) addresses the urgent need for Martha’s Vineyard to address climate change because of its impact on the island’s climate and coastline. Having island residents switch to renewable resources can create a great feeling in the community that they’re all in this together.

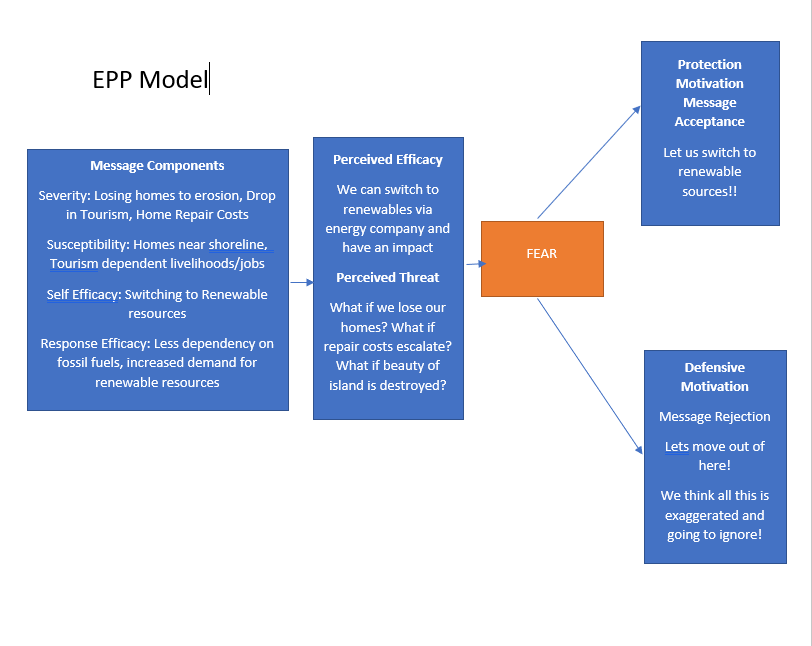

Extended Parallel Process Model

Using the Extended Parallel Process Model, we can use fear appeals to drive the behavior change that we are looking for. In this case, our threat information will center around the impact of climate change to the local environment. By showing that residents in Martha’s Vineyard are both susceptible to the effects of climate change, and that those effects can be severe, we can generate enough fear to motivate behavioral change with the introduction of efficacy information.

In order to be successful, severity information should show that the negative outcomes of not addressing climate change are bad enough to warrant action. Potential impacts could include losing a home to erosion, reduced economic impact from a drop in tourism due to an increase in weather events and increased costs to repair infrastructure. An analysis of sea level rise in nearby Nantucket and Wood’s Hole found that “while there was some uncertainty as to precise rates, it was evident that sea levels in the vicinity of Martha’s Vineyard are rising” (Bouillette-jacobson, 2008, p. 332). Bouillette-jacobson estimates that sea levels will rise 0.3 meters to 0.58 meters, possibly as high as 1.14 meters by the year 2100. Furthermore, an analysis showed that the south side of Martha’s Vineyard was at significant risk of future erosion. “Ultimately, a coastal island may never reach a sustainable level in perpetuity because of all the natural and manmade forces acting upon it. The best that can be hoped for is that, with long-term planning, the inhabitants of Martha’s Vineyard will safely retreat from the island, rather than attempt to guard themselves against the forces of the ocean” (Bouillette-jacobson, 2008, p. 348-349).

To generate enough fear, a campaign can not have severity information alone. Susceptibility information must exist to show the target audience that they are at risk to the perceived severe outcomes. In a 2012 study of climate vulnerability in Dukes County, where Martha’s Vineyard is located, Pollak (2012) wrote that the major economic drivers in the area, commercial fishing and seasonal tourism, are reliant on the ocean and can be severely impacted by rising sea levels, increased weather events and other effects of climate change. Pollak goes on to calculate both a social vulnerability score and climate vulnerability score (based on potential sea level rise and storm surge events), finding that the eastern parts of Martha’s Vineyard had the highest concentration of social and climate vulnerability. “Overall it seems that the flatter, low lying towns down-island have been more conducive to development, which is vulnerable to hazards associated with climate change” (Pollak, 2012, p. 37).

Once we have generated fear in our target audience, we must supply efficacy information to have them engage in the positive adaptive change (danger control process) of asking their energy provider to source their energy from renewable sources. Drennen et al. (1996) found that a 50% shift in power generation to solar from fossil fuels would reduce carbon dioxide emissions 10% in 20 years and 35% in 50 years. A study of large scale solar power installations considered 32 potential environmental impacts. “Of the remaining 10 impacts, 4 are neutral, and 6 require further research before they can be appraised. None of the impacts are negative relative to traditional power generation” (Turney & Fthenakis, 2011, para 1). In supplying self-efficacy information, we can provide messaging that will show them that they are capable of taking the action necessary to make a positive change. Messages such as “It’s as easy as calling your energy provider” or “Keep Martha’s Vineyard Green” could be used to both show how simple this first step can be and what effect it can have on the environment.

Visual Map

References

American Psychological Association, APA Task Force on Climate Change. (2022) Addressing the Climate Crisis: An Action Plan for Psychologists, Report of the APA Task Force on Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/science/about/publications/ climate-crisis-action-plan.pdf.

Axsen, J. (2014, December). Citizen acceptance of new fossil fuel infrastructure: Value theory and Canada׳s Northern Gateway Pipeline. Energy Policy, 75, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.10.023

Bang, H. K., Ellinger, A. E., Hadjimarcou, J., & Traichal, P. A. (2000). Consumer concern, knowledge, belief, and attitude toward renewable energy: An application of the reasoned action theory. Psychology & Marketing, 17(6), 449-468.

Benjamin, Lisa; Bhargava, Akriti; Franta, Benjamin; Martínez Toral, Karla; Setzer, Joana; and Tandon, Aradhna. 2022. “Climate-Washing Litigation: Legal Liability for Misleading Climate Communications.” Policy Briefing, The Climate Social Science Network. January 2022.

Brouillette-jacobson, D. M. (2008). Analysis of Coastal Erosion on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts: a Paraglacial Island [MA thesis]. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Brulle, R. J. (2019). Networks of opposition: A structural analysis of U.S. Climate Change Countermovement Coalitions 1989–2015. Sociological Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12333

Drennen, T. E., Erickson, J. D., & Chapman, D. (1996, January). Solar power and climate change policy in developing countries. Energy Policy, 24(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-4215(95)00117-4

Emberger-Klein, A., Schöps, J., & Menrad, K. (2021, December 14). The Influence of Climate Attitudes and Subjective and Social Norms on Supermarket Consumers’ Intention Toward Climate-Friendly Food Consumption. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.764517

Forbush, J., & O’Shea, T. (2021). (rep.). State of the Coast: Future Climate-Driven Risks — And Their Solutions — On Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket And Gosnold (Elizabeth Islands).

Gregersen, T., Doran, R., Böhm, G., Tvinnereim, E., & Poortinga, W. (2020). Political Orientation Moderates the Relationship Between Climate Change Beliefs and Worry About Climate Change. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1573. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01573

Hansla, A., Gamble, A., Juliusson, A., & Gärling, T. (2008, February). Psychological determinants of attitude towards and willingness to pay for green electricity. Energy Policy, 36(2), 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2007.10.027

Kennedy, B., Tyson, A., & Funk, C. (2022, July 19). Americans Divided Over Direction of Biden’s Climate Change Policies. Pew Research Center Science & Society. Retrieved October 2, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/07/14/americans-divided-over-direction-of-bidens-climate-change-policies/

Lazrus, H. (2012). Sea change: Island communities and climate change. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41(1), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145730

Lei, Z., Jingxiao, J., & Ruyang, L. (2011). Research on the consumption mode of green electricity in China-Based on theory of reasoned action. Energy Procedia, 5, 938-944

Li, H., Jenkins-Smith, H. C., Silva, C. L., Berrens, R. P., & Herron, K. G. (2009, January). Public support for reducing US reliance on fossil fuels: Investigating household willingness-to-pay for energy research and development. Ecological Economics, 68(3), 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.005

Martha’s Vineyard Commission. (2010). (rep.). Island Plan: Charting the Future of the Vineyard. https://www.mvcommission.org/sites/default/files/docs/Island_Plan_Web_Version.pdf

Millard-Ball, A. (2012). Do city climate plans reduce emissions? Journal of Urban Economics, 71(3), 289–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2011.12.004

Nguyen, Q., Hens, L., MacAlister, C., Johnson, L., Lebel, B., Bach Tan, S., Manh Nguyen, H., Nguyen, T., & Lebel, L. (2018, June 14). Theory of Reasoned Action as a Framework for Communicating Climate Risk: A Case Study of Schoolchildren in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. Sustainability, 10(6), 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062019

Olson-Hazboun, S. K. (2018, July). “Why are we being punished and they are being rewarded?” views on renewable energy in fossil fuels-based communities of the U.S. west. The Extractive Industries and Society, 5(3), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.05.001

Oswald, Y., Owen, A. & Steinberger, J.K. Large inequality in international and intranational energy footprints between income groups and across consumption categories. Nat Energy 5, 231–239 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0579-8

Perloff, R.M. (2017). The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century (6th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315657714

PD43+ 2020 president General Election Statewide (showing only Dukes County). PD43+ Massachusetts Election Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://electionstats.state.ma.us/elections/view/140751/filter_by_county:Dukes

Pollak, J. (2012). An Integrated Approach for Developing Adaptation Strategies in Climate Planning: A Case Study of Vulnerability in Dukes County, Massachusetts [MA thesis]. University of Connecticut.

Turney, D., & Fthenakis, V. (2011, August). Environmental impacts from the installation and operation of large-scale solar power plants. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 15(6), 3261–3270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2011.04.023

Tyson, A., Funk, C., & Kennedy, B. (2022, March 1). Americans Largely Favor U.S. Taking Steps To Become Carbon Neutral by 2050. Pew Research Center Science & Society.

Tyson, A., Kennedy, B., & Funk, C. (2022, April 28). Gen Z, millennials stand out for climate change activism, social media engagement with issue. Pew Research Center Science & Society. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/05/26/gen-z-millennials-stand-out-for-climate-change-activism-social-media-engagement-with-issue/

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). State-level wealth, asset ownership, & debt of households tables: 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/wealth/state-wealth-asset-ownership.html

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2022, March 4). What is U.S. electricity generation by energy source? Electricity in the U.S. – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/electricity/electricity-in-the-us.php

Way, R. (2022, September 21). Empirically grounded technology forecasts and the energy transition. Joule. Retrieved September 30, 2022, from https://www.cell.com/joule/fulltext/S2542-4351(22)00410-X

Zander, F. (2018, November 21). Climate Change Risk Perception and Pro-Environmental Behavior. Toward a Comprehensive Model. Grin Verlag.

Zhang, X., & Caldeira, K. (2015). Time Scales and ratios of climate forcing due to thermal versus carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels. Geophysical Research Letters, 42(11), 4548–4555. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015gl063514